This is a story about a woman who is changing her world, and the children whose lives she is transforming.

Seven years ago, Cathy Groenendijk made a distressing discovery in the town of Juba where she worked for an international humanitarian organization.Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me. – Matthew 25:40

Young girls. Working and living on the streets, in the slums, in cemeteries. Selling things, scavenging from the garbage or wandering around the market. Some of the girls were orphans or had lost contact with their parents. Some parents encouraged their daughters to sell themselves for money.

“They were dirty, full of sores,” Cathy remembers. “You’d find a child who was ill on the street, filthy, without any life skills. They were only accustomed to violence, to hunger, to neglect, to rough language, to being abused, and alcoholism, sniffing glue to survive on the street.”

Cathy is not the kind of person who sees a problem and does nothing. “I discovered that this area had such a big need. I knew there was nobody.”

Cathy helps the children try on donated clothes.It started slowly. She felt that she had to do something, so Cathy began by bringing a few of the girls into her home for daily meals. They were malnourished, emaciated, and in desperate need of a wash. “I started with three kids, then eventually it became 5, then 10, 15, 25, 50. We identified a lot of children on the streets, and realized that the children, especially girls, were being sexually abused, and realized also that they needed a home. If you gave them material for school, the next day they didn’t remember where they kept them, wherever they slept. And that’s why this center was started. Slowly over seven years we’ve built up this place and it has become a safe place for these children.”

‘This place’ is now a center that can house up to 60 of the most abused or vulnerable children in dormitory-like accommodation. It is called “Confident Children out of Conflict”, or CCC, and the program has grown to support over 600 children from the slums through paying for school fees, uniforms and school materials. CCC actively advocates for the protection and rights of vulnerable children as well, and justice against abuse and neglect.

The Rough Years

These sweet little toothpick girls were all of a sudden pounding each other.

Taking these girls off the street is not easy. They don’t turn into sweet, well-behaved children overnight, and sometimes never do. Often their way of dealing with trauma is to act out in hatred toward the very person who is helping them. Cathy accepts their struggles and hatred as part of the healing process, but it is tough.

“The children fight a lot the first three years here. They fight everybody. They only know about violence in their lives. They don’t even talk, they hit. So that is tough, and it exhausts you because you’re all the time dealing with the children in a negative sense. I looked 20 years younger until I started working with these girls,” Cathy laughs. “They exhaust your mind. The demands for boys are less. The worry is less. Boys get abused as well, but it’s not obvious. Girls get abused.”

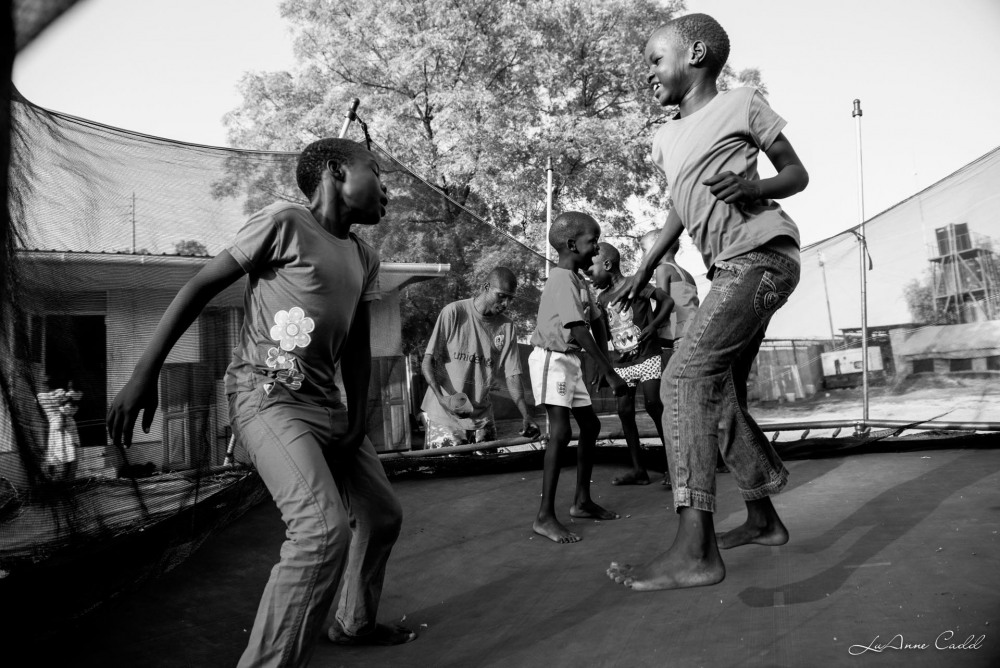

Three girls fight over a swing at the CCC compound.Many members of the MAF South Sudan staff have been volunteering their time at CCC over the years since Cathy began the program. Kristen Unger started a reading group to help the girls aged seven to ten with their English back in 2010, meeting twice a week.

“They were rough!” Kristen remembers. “We would sit around a little table in the courtyard and I had about eight girls at the most. We’d be working on something and all of a sudden, two of them would literally be in a fistfight. And the others would jump on top. You had girls rolling on the cement floor. These sweet little toothpick girls were all of a sudden pounding each other. They were straight off the street! They didn’t know how to get along with each other, let alone how to sit and learn anything. It was a real challenge.” Kristen laughs at the memory of this scene. “It was pretty intense.”

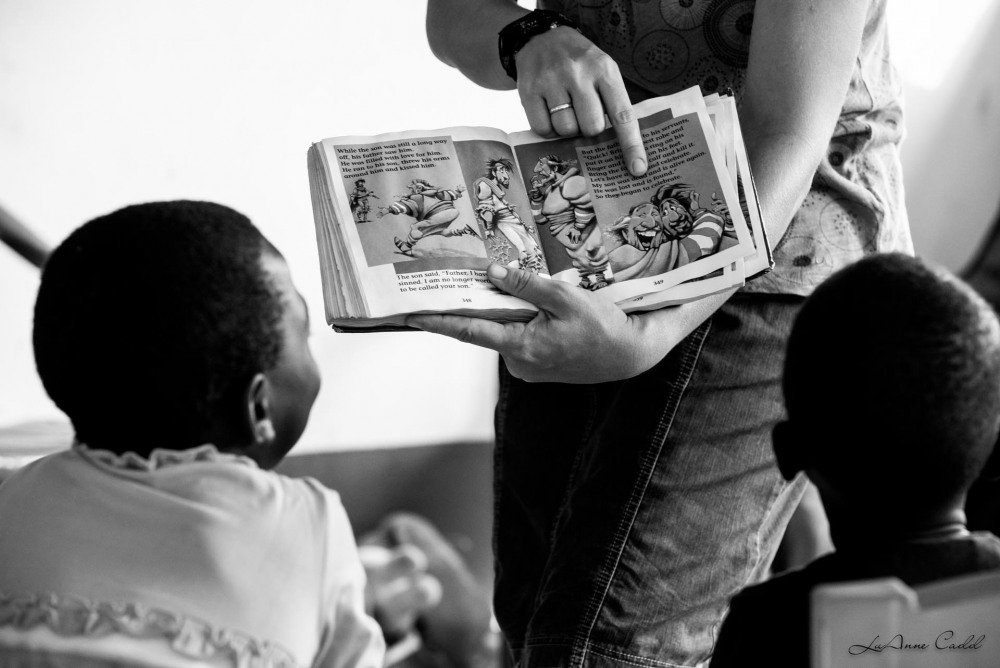

Kristen Unger reads to the CCC girls.One of the most difficult parts for Cathy is when they receive children who have been terribly abused or are infected with HIV. But perhaps the most painful is when a child who has been doing well drops back. Sometimes a girl in the program, either supported on the outside or living at the compound, will run away or get pregnant. It breaks Cathy’s heart. Recently “Annabel” ran away and was found eight days later. On the CCC Facebook page, someone asked why she ran when she finally had a safe place and plenty of food. “She is still new at the centre,” CCC responded, “and she is not used to an organised life and authority. She thinks that begging is easier than working hard on learning. It takes at least a year before the girls get used to structured life. She is in a transitional stage.”

Home is a Cemetery

These girls, almost 100% sure, if we didn’t take care of them, their only option would be to sell themselves because they have nothing.

Juba, the largest city and capital of South Sudan, is a magnet for people fleeing from violence or seeking better opportunities from outlying states, but it has not offered this kind of refuge to very many. Juba itself has experienced horrific ethnic violence, and the poor often become poorer.

After the war when the city began to build and grow, many of the desperately poor and displaced who camped along the river were forcibly moved off the land to make way for hotels and restaurants. They settled nearby at a large old cemetery where some had already made their home between the gravesites. Over the last few years, the population in the cemetery has grown to an estimated 800 with people living in shacks or under tarps, using the flat gravestones for drying dishes or hanging out wet clothes. As the rains come, many live in ankle-deep water or mud, nearly as wet inside as they are outside.

This is just one place where many of the CCC-supported children live with parents, relatives, or alone.

With so much need, CCC chooses girls to live at the compound when there is imminent danger or evidence of abuse or sexual exploitation. In September 2013, the French Embassy and CCC jointly conducted a survey of street girls, discovering that out of 159 surveyed, 31 were victims of commercial sexual exploitation. That number is growing, according to Al Jazeera. Out of an estimated 3000 street children, up to 500 could be involved in child prostitution.

Much of the problem can be traced to the breakdown of family during the war. Internally displaced families or children who have lost their parents have no means to care for themselves which often leads to sexual exploitation.

“These girls, almost 100% sure, if we didn’t take care of them, their only option would be to sell themselves because they have nothing,” Cathy guarantees.

A Child Transformed

I cried. I thought, wow. It’s high time I destroyed all those photographs.

Cathy’s work may be difficult and sometimes discouraging, but she has an immediate response, without hesitation, on why she does this.

“There is a girl who we got from the market,” she begins. “She was very filthy and really was so abused. I’ll call her ‘Mary’. She is now 16 years old, but before, when we used to tell these stories, she came and looked at me in the face and said, ‘Mommy, did you really get me from the market? Was I really selling eggs?’ And I cried. I thought, wow. It’s high time I destroyed all those photographs and not tell them these stories. She doesn’t remember any of it anymore. And for me it’s as clear as day what she was before. And then I realized that yes, this is what I wanted.

“And when one of the girls passed exams and went to the teacher training college, I think it’s wonderful when I see one child transformed. We got a child from the garbage who just lived like an animal, used to live in the bushes around. But eventually when she embraced sleeping in a bed, getting up in the morning and dressing up, that is wonderful. When you see children being transformed, lives are being transformed.”

Cathy walks through the dorm building with three of the teenage girls, ‘Lizzie’, ‘Regina’, and ‘Nancy’, in the middle of the afternoon when most are outside playing. The rooms are empty of people, but spotlessly clean and tidy with three bunk beds per room. Cathy points out the stuffed animals that decorate most of the nicely made beds.“They love the toys so much,” Cathy says. “They make the beds every day and then they decorate.”

She glances into another room down the hall. “Whose bed is this? Nancy! You should be making your bed.” Cathy is laughing and teasing Nancy now. “Lizzie’s is down there. We’ll see if you made your bed, Lizzie!” The girls giggle as they walk down to Lizzie’s room to see her perfect display of toys. She sits on her bed and picks up the biggest one, hugging it to her chest. Regina’s bed is unmade.

Lizzi sits on her bed with her stuffed animals.“Regina was one of the children we were supporting in the community,” Cathy explains, “but when she became 14, her family, her brothers, wanted to force her to get married. Actually, they went to school and threatened everybody. She’s here for protection against forced marriage. Regina has been here for two years.”

Sixteen-year-old Lizzie was living in the cemetery, but there were reports that men wanted to exploit her sexually so Cathy brought her to the compound for protection.

Lizzie is shy. She won’t say much about how this place is different from the cemetery. “It’s a good place to stay,” she says softly. Cathy presses her for more. “This is different because of the water there,” Lizzie continues in her broken English. “No good place in the house. Where we sleep is not good. When it rains, it floods in the house.”

“Even when they are sleeping, sometimes the floods come and it can sweep them away,” Cathy elaborates. “They also sometimes sleep in the open using old sheeting.”

Cathy asks Lizzie what she wants to do when she grows up. “I want to work as a designer, with beads,” Lizzie says, without hesitation.

“She can design bracelets and clothes,” Cathy says proudly, like a mom. “She’s good. She’s an artist. The girls are now selling their jewelry to get a bit of money. One of the girls said to me, ‘Wow, if I don’t get a job in the future, I’m going to earn money from making beads.’ For me this is better than anything in the world! Better than whatever someone could ever give to me.”

Good Neighbors

Cathy grabs you with both arms, pulls you in, and you’re 100% committed.

Walk out of the MAF Juba gate, turn left down a walking path for about two minutes, and you will be at the entrance to the CCC compound. The two organizations are quite literally neighbors. But for many years now, it has gone far beyond proximity.

“MAF is helping us a lot wherever it’s possible,” Cathy says. “They supported over 50 children with paying school fees – $400 per child. They have airlifted two children to Nairobi who needed medical care. They brought solar panels for us from Nairobi, and their technicians sometimes help us. They built the wall. Lots of people who work for MAF also volunteer here, like Judith – she’s coming here as a counselor and helping the children. We also have Phil who is helping us with technical/electricity things. One of the IT persons has been playing games with the children. Kristen Unger was teaching them English. Christine Hageneier was the one who mobilized a lot of MAF all over the world and told the stories. She took in one of the girls who was being sexually abused, a little girl who was less than eight. We have a couple, Elger and Sonja Nieuwenhuis who are supporting us in fundraising and volunteering here, teaching the children on Sunday. Elger is helping with finance, and of course they help with the other kids. MAF is a very, very special partner for us. They are very good neighbors.”

Sonja Nieuwenhuis teaches Sunday School to the younger CCC children.It’s clear when speaking to the MAF staff that they love Cathy, love the children, and are passionate about helping. Besides teaching basic English to the young girls in earlier days, more recently Kristen Unger hosts a slightly older group now in her home twice a week and helps teach the Sunday School class for the CCC girls. She’s been able to see the change in the girls over time.

“As a group they have grown so much compared to those early days when they couldn’t even sit around a table without having a fist fight, to now where they really are quite well-behaved when they come here. Cathy tells me they aren’t always like that, obviously. But just to see what Cathy has done with them. The influence of all these people who have invested in them. God has been really faithful. You can see the difference in the girls.”

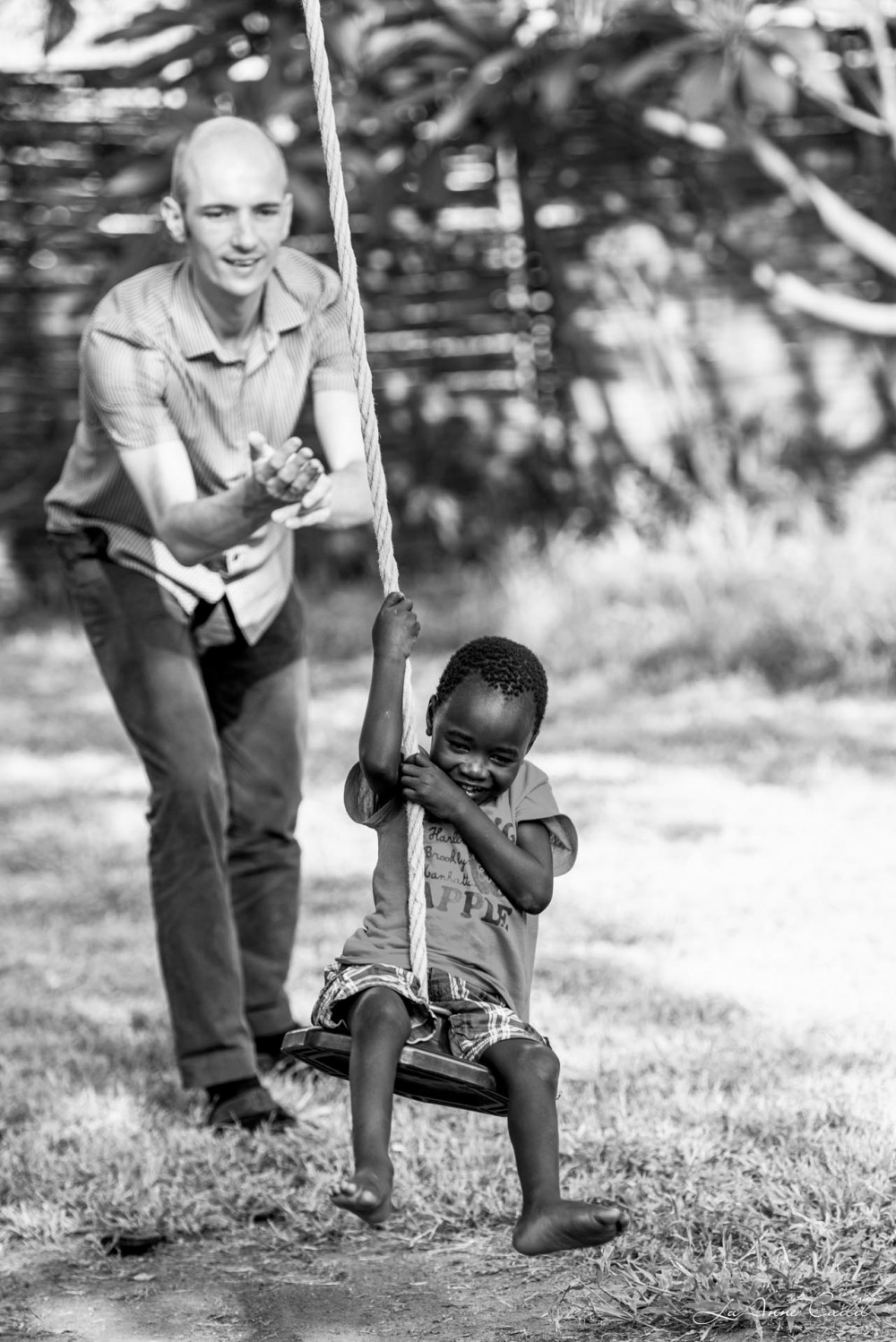

Elger Nieuwenhuis, MAF South Sudan’s financial director, and his wife Sonja, are deeply invested in the children at CCC, as well as supporting families in the slums and cemetery, and providing care packages. They also foster a small boy, Moses, who came to CCC as a severely malnourished one-year-old baby that no one thought would survive. Moses is now a lively, healthy child who speaks both English and Dutch, and just celebrated his fourth birthday.

Elger and Sonja play with their foster son Moses, now 4 years old.“We (at MAF) all joke that if you’re even considering volunteering, once you say you’ll do anything, Cathy grabs you with both arms, pulls you in, and you’re 100% committed,” Kristen explains, laughing. “If there’s anybody in Juba who can get something done, it’s Cathy. Her commitment is incredible. If she sees a need, she’ll do whatever she can, bend over backwards to help. Like Michael, right now.”

Michael

On 16 December 2013, 15-year-old Michael walked to school, wearing his uniform. When he found no one there, he walked home to discover the house of his brother empty as well. Both his parents had died when he was young and his married 22-year-old brother had become his care-taker.He mostly remembers thinking, “Why would they shoot a boy wearing a school uniform?”

Michael knew something was wrong. The evening before, gunfire could be heard across the city. Before Michael had time to think, six armed men entered the property and began to harass him, speaking only in Dinka. Because Michael is Nuer, he remained silent. He didn’t understand. It was a grave handicap.

One of the men shot him in his left leg. He tried to run but was shot in his other leg leaving him bleeding on the ground. His memory is unclear at this point. He mostly remembers thinking, “Why would they shoot a boy wearing a school uniform?” A man came by and helped get Michael to a hospital.

For the next three months, Michael remained in the hospital for several operations to save his leg where the bone had been damaged. With no idea where his brother was, and nowhere to go, someone asked Cathy if she would take him to live at the CCC compound. Having an older boy on a compound with abused teenage girls was not something Cathy would normally do, but Michael was immobile and he had no one. She said yes.Over the next few months, Michael’s leg got infected. He had another operation, but it wouldn’t heal and the pain wouldn’t go away. There was more that needed healing than just his leg, though.

Judith DuPuis, wife of MAF’s Operation Manager for South Sudan, had just returned to Juba from an extended trip to Canada. It was Sunday morning, and following the church service, people gathered around a table outside for tea and treats. Judith, Michael, the pastor, and a few others sat in a circle talking, and someone suggested they pray together. As each person began to hold hands around the table, Michael refused to take the hand of the man sitting next to him, a Dinka.

“He said, ‘No, I don’t want to,’” Judith remembers. “It was a real awkward moment for everybody. We were saying ‘That’s OK.’ Up to that point I hadn’t heard Michael’s story. He started to cry. It was obvious he was hurting.”

Judith went to see Michael later that day and every day that week. She listened to him talk and cry. She read the story of Job and how he also didn’t understand what was happening to him, but he stayed faithful to God. “We also read through the part in Acts where Stephen was murdered,” Judith recalls. “And as he was being stoned, he prayed to God to forgive those who were stoning him.”Michael told Judith where he came from originally and the name of his brother. That week, a pastor who was from Michael’s home county came into the MAF office. It seemed a bit crazy, but Judith mentioned that she was looking for a boy’s brother named Peter Bader. To Judith’s shock, the pastor responded, “I have this man’s name in my phone contact list!” Judith arranged for Michael to speak to his brother after six months of no contact. Peter had fled to the UN base for protection and had been living in the squalid IDP camp ever since.

“Michael’s demeanor changed. You could see that he was so much happier. He didn’t know if his brother was dead or alive,” Judith said.

Judith and Michael continued with the Bible stories, including the story of Saul who persecuted the Christians, only to become a Christian himself and be forgiven by God.“At the end of those Bible stories,” Judith said, “Michael could see that anger that hurt doesn’t come from God. He could very clearly see the miracle of being able to speak with his brother. I asked how he would feel about praying with that man at church and he said, ‘I would be fine.’ I asked what made him change his mind and heart, and he told me simply, ‘God has.’”

Through Cathy’s efforts and networking, she was able to find donors who paid for Michael to travel to Nairobi in September for major surgery on his leg, avoiding an inevitable amputation had this intervention not happened. The surgery went well, and he is recovering in Nairobi.

For the Least of These

What if there were more people who are thinking that this is what God really wants everyone to do, and everybody did their bit?

Cathy’s drive comes from her relationship with Christ and conviction that Jesus meant it when he said that whatever we do for the least of these, we do it for Him.

“When you see that you have given a chance and a future to a child, this is wonderful. And I think this is what God wants us to do. I think this is the work of Christians and the church that they should be doing. And we should always be conscious that we’re doing it for Christ. For me that is the biggest motivation. I live my life as a Christian in practice.

“There’s a lot of suffering in the world everywhere, but if you think that I started this program, and I’ve been a blessing to so many children, what if there were more people who are thinking that this is what God really wants everyone to do, and everybody did their bit? I think we would reduce a lot of suffering in the world around us.”

Wow! Thanks for sharing! God bless Cathy and the others who are ministering to these children!

Inspiring! Thanks for sharing her story.

Dear Lu 🙂

Think you for this storkes.

We Will prayers for the children.

Have A look ón http://www.maf.dk and Reading last issue of Flight Mission

The article from Beroroha with all your brilliant Photoshop.

With love

Kamma & Arne

Thank you for sharing this wonderful story of the grace and mercy of God worked out through Cathy and your MAF colleagues.

OMG, Lu:

You are killing me with your fantastic photos!! Found this blog post, which I had missed while looking for something posted for B&W challenge on FB – it’s all here; but better in context. The stories and the photos are so powerful. When are you going to do an actual book? I think the time has come.

Wow, thanks Barb. You’re too nice. No plans for a book, I’m afraid. And that B&W challenge thing will have to wait a week. You’ll need to remind me.